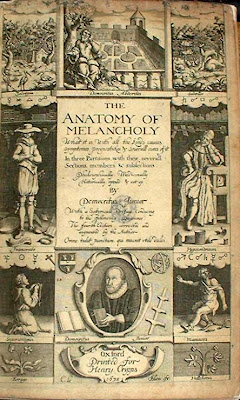

Anatomy of Melancholy

Now last of all to fill a place, /Presented is the Author’s face; /And in that habit which he wears, /His image to the world appears. /His mind no art can well express, /That by his writings you may guess. Burton, Anatomy of Melancholy, from The Argument of the Frontispiece

Anatomy & the Database Genre

But for such matters as concern the knowledge of themselves, they are wholly ignorant and careless; they know not what this body and soul are, how combined, of what parts and faculties they consist, or how a man differs from a dog. Burton, Anatomy of Melancholy, “Division of the Body” (Pt. 1, Sec. I, Mem. II, 146-147).

We see—Comparatively. Emily Dickinson.

Digital humanities research has only recently begun to consider database as a genre. In order to describe digital media such as database or digital archives, scholars must resort to metaphors, such as Deleuze and Guattari’s rhizomes, Borges’s labyrinths or library, and Jerome McGann’s fractals. Northrop Frye argues that “in every age of literature there tends to be some kind of central encyclopaedic form, which is normally a scripture or sacred book in the mythical mode, and some ‘analogy of revelation’” in other modes (315).

In our current age, the central, encyclopedic form consists of database, a term I will use interchangeably with digital archives, a move that requires some explanation. I use the term digital archive to differentiate digital from physical collections, and by digital archive I mean literary digital archives—specifically, databases with the purpose of collecting literary texts or manuscripts, correspondence, and ephemera written by or pertaining to documents created and used by authors who are part of the “literary world.” Folsom comments that we often “hear archive and database conflated, as if the two terms signified the same imagined or idealized fullness of evidence” (“Database” 1575). Jerome McGann criticizes Folsom’s use of the term database, and Folsom replies that the Walt Whitman archive is, in fact, a database, when database is defined as “a vast vault of unseen data that are retrieved and organized by our metaphoric commands” (1609). It is impossible to write or talk of these archives without metaphors—namely words associated with print conventions and physical archives (as in Folsom’s “vast vault” in the previous sentence).

Manovich is less concerned with the technical types of databases than with their cultural implications, so his definition of database acknowledges the computer science definition while developing an argument about the social and cultural effects of database on narrative and on database as a genre. He contends that every web site is, in fact, a sort of database. The exchange between Folsom and McGann later prompts Price to argue that “in the course of denying the applicability of ‘database’ as a term suitable to the Whitman Archive, McGann overlooks that our search engine is entirely dependent on translating XML files into database form” (“Edition”). Price contrasts the “strict definition” of database as a technical term referring to a “collection of structured data that is managed by a database management system, most commonly based on a relational model,” and a “looser” definition that works metaphorically (“Edition”). At odds is how technical and precise to make the term database, and like Folsom, Price, and Manovich, I use the term metaphorically.

Ed Folsom argues that database is a new genre of the twenty-first century, but I argue that it is, instead, a manifestation of an old genre, the anatomy. I offer the metaphor of anatomy to describe the database genre not as just another trope to add to the list of metaphors, but as a generic inscription with historical and methodological implications. Kenneth Price suggests the term arsenal as a term for literary digital archives because the word derived from an Italian word for “workshop,” a term that emphasizes craft; the problem with the term, according to Price, is its militaristic connotation (“Edition”). While the term arsenal brings with it an etymologically-meaningful history and the emphasis on creation, I believe the term anatomy provides a richer metaphorical basis from which to consider literary databases. Because digital humanities scholarship is under development, any application of terminology presents a problem. Price discusses the current instability of terms for electronic scholarship and how our terms are inadequate, calling for a “new term that is vivid enough to be memorable, elastic enough to cover a class of like things, and yet restrictive enough to allow us to include some scholarly undertakings and not others” (“Edition”). Anatomy is such a term.